In an increasingly globalised world, mobility has become a defining characteristic of human existence. People are constantly on the move, whether it be for economic reasons, seeking refuge, pursuing personal aspirations, or owing to climate disasters. The current global estimate is that there were around 281 million international migrants in the world in 2020. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on mobility and migration trends is now seeing recovery with the first three months of 2023 witnessing 235 million tourists travelling internationally. At the same time, as of May 2022, 100 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide due to persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations – more than double the number recorded in 2010.

In turn, all types of mobility movements increasingly hinge on digital interactions – systems of identity, payments, and communication. A student moving to London for pursuing her post-graduate diploma will interact with the digital admissions, visa, telecommunications, housing and even payment systems in her mobility journey. The by-product of these digital interactions is the collection and generation of large amounts of data (such as personal details, biometrics, financial information, cultural and family background, health information, call records, geo-location, social media usage and more).

Data is the fundamental infrastructure that sustains all digital interactions – it is the core input, crucial to the function of interaction, and an eventual output or exhaust. Currently, the distribution of value from these infrastructures back to the communities is unclear. There have also been instances where digital systems for migration have adversely impacted the groups they aim to empower or protect. Therefore, how these systems are deployed and how the data is governed impacts the benefits, extent of empowerment, potential for harm and vulnerability of mobile populations. Most data on people on the move is collected passively, through their largely informal use of social platforms and the digital traces they leave behind by using phones and other technologies — whether it be an individual’s geo-location social media data and online media content or internet activity (such as Google searches). Another set is collected through more formalised channels by governments and institutional entities — including biometric (fingerprints, facial images) and border data collection systems; visa, residence and/or work permits; criminal records; health records; and more. At any of those junctures, there is limited visibility on how such data is used, may be used, by whom, or even to what ends.

This widespread presence of data infrastructures does not guarantee equal access or benefits for all and creates limited agency for data subjects over their data. People on the move often face significant challenges when it comes to negotiating or drawing value from digital systems. This results in a spectrum of disempowerment ranging from hyper-surveillance to complete invisibilisation. Several Rohingya refugees living in Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh, have been targeted by the police for posting about instances of harassment at the refugee camp — leading to the confiscation of laptops and flash drives, and posting photos (without consent) of individuals on social media that aid in framing of criminal charges against the refugees. At the same time, a lack of data on many people on the move lends to invisibilisation of the risks and vulnerabilities they face. The plight of migrant workers in India during the Covid-19 crisis was exacerbated by a lack of data on how many people were on the move, how many reached their final destination, and how many did not survive? Such incomplete information makes it challenging to design adequate policy responses and impacts data-driven decisions. Lack of transparency, discriminatory practices, and the potential for misuse of data undermine the agency and rights of mobile populations.

Moreover, novel digital systems are regularly being tested and deployed across the world to better control and monitor mobile movements. But how humans, particularly vulnerable groups, interact with these systems remains largely opaque. These challenges are particularly pronounced in the context of mixed migration, where people traverse borders for a host of reasons (combining voluntary and involuntary movement) and therefore do not fall neatly into traditional classifications of migrant or refugee. Consequently, there is also an impetus to understand the correlation between their vulnerability and digital interactions. To address this gap, Aapti Institute is launching a year-long research initiative on exploring and understanding the intersectionality of human mobility and data rights. Supported by the Robert Bosch Foundation, the initiative aims to:

- Map the landscape of data infrastructures in the context of mixed migration. This involves identifying the types and points of digital interactions that intersect with the mobility journey of people on the move.

- Unpack people’s access and ability to negotiate with data infrastructures. We seek to identify the barriers that impede the ability of mobile populations to harness the full potential of digital interactions.

- Build pathways for the governance of data infrastructures such that it empowers mobile populations. By engaging with varied stakeholders, the aim is to design governance frameworks that protect data rights and ensure equity, inclusivity, transparency, and accountability.

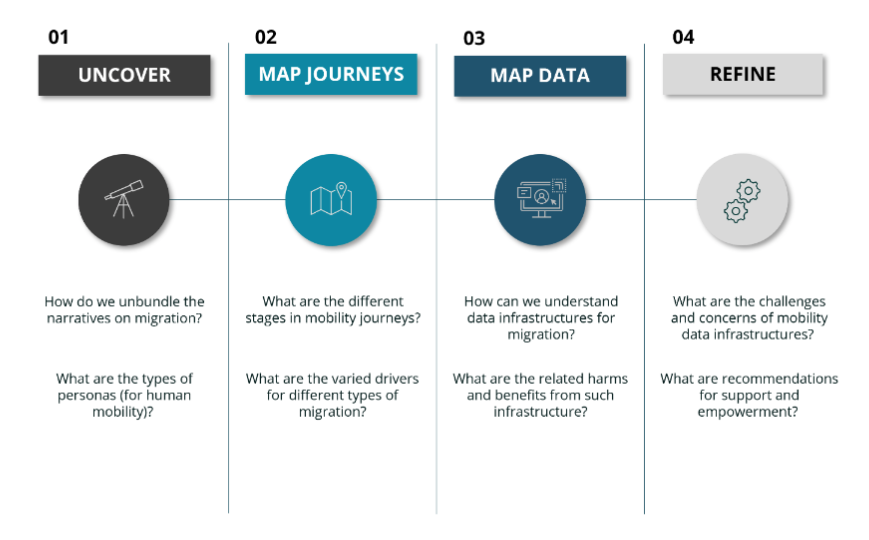

Given the complexity of the research, we have designed a tiered approach to help us unpack the impact of digital infrastructures on human mobility, as is detailed in Figure 1 below.

Through the course of this initiative, we aim to gain insights into how we can embed fairness in the way people are made visible, represented, and treated as a result of the data in their digital mobility journeys. As this work evolves, we also aim to unpack the principles and design required to create equitable infrastructures and governance mechanisms for human migration, through an analysis of existing modes of governance and their related harms.

In this emerging field of study, we are curious and eager to engage with experts from various stakeholder groups who are interested in this work and would like to exchange insights on these questions. If you, or anyone you know, work in the areas of human mobility, data infrastructures and/or the intersection between the two, please write to us at [email protected] and we would love to schedule some time with you to talk.

**Photo by Sébastien Goldberg on Unsplash