Executive Summary

In 2020, Aapti released a report that set out a taxonomy of data stewardship, a paradigm of data governance that seeks to centre individuals and communities in the collection, usage and sharing of data. The discourse of data stewardship we’ve been building on since then has put forward frameworks and best practices for how intermediary entities can support individuals and communities in deriving value from data – to empower, advocate for and serve as a tool for negotiating and accessing rights – both online and offline.

While stewardship has since gained significant traction (particularly models like data trusts and data cooperatives) from researchers, policymakers and practitioners alike, it is still characterised as an emerging field.

This calls for greater focus on unpacking how stewardship may be best translated into practice. Our Stewardship Navigator tool attempted to address this in part – and sought to provide stewards or steward-like initiatives with a set of questions and possible design choices to consider.

After the release of this tool, however, we learned that many of these choices are influenced and predicated on sector-specific nuances, requirements and realities. We understand that the aspiration of building participatory data governance systems is critical to pursue, but the contours of what participatory stewardship is and is not for different stakeholders, and how participation can be actualised needs to be understood further.

Based on our research over the last three years, even considering plurality across steward model types, shaping responsible data governance requires careful designing and strategizing on multiple levels – technical, community, policy and partnerships. Further, defining pathways, degrees and mechanisms to enable participation also vary, with certain domain-specific examples providing blueprints for civil society and the public sector to uphold participatory ethics. As data privacy and governance frameworks evolve globally, there is a need to situate the role of a steward and understand what needs to be put in place to create responsive regulation. There is a need to diagnose how various stakeholders intersect and what their roles may be in the ecosystem.

To deepen our insights and recommendations, we also chose to identify key sectors where stewardship may prove to be most actionable and valuable:

Environment & Sustainability

Healthcare

Urban Governance

How to read this Document

The Introduction section provides a general overview of the concept of data stewardship, the notion of participation in data governance, and the aim behind drawing up this playbook. There are also introductions for each of the three sectors which delineate the value proposition of participatory mechanisms for data governance within that sector with an examination of the overarching concerns in the governance of that sector.

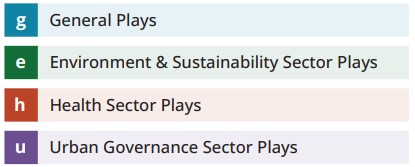

As there is a set of Plays that are sector-agnostic, as well as Plays for each of the three sectors, along with a number of challenges and strategies within each Play, we have used the following set of codes for easy reference inside and across Plays, Challenges and Strategies in each sector.

Each Challenge will be represented by a 3-character code, where the first character refers to the relevant sector, the second refers to the Play number, and the third refers to the challenge number.

For example: Challenge h2.3 refers to Health Sector, Play 2, Challenge 3

Similarly, each Strategy will be represented by a 4-character code, where the first character refers to the relevant sector, the second refers to the Play number, the third refers to the challenge number and the fourth refers to the strategy.

For example: Strategy h 2.3.1 refers to Health Sector, Play 2, Challenge 3, Strategy 1

The table below sets out what strategies are relevant to which category of stakeholder.

General Plays

Stewards / Steward-like Initiatives

Play 0

Play I

Play II

Play III

Policymakers & Public Sector Actors

Play 0

Play I

Play II

Private Sector

Play I

Play II

Technologists

Play II

Funders

Play I

Play II

Environment & Sustainability

Stewards / Steward-like Initiatives

Play I

Play II

Play III

Policymakers & Public Sector Actors

Play I

Play II

Play III

Private Sector

Play I

Play II

Play III

Technologists

Play I

Play II

Funders

Play I

Play II

Healthcare

Stewards / Steward-like Initiatives

Play I

Play II

Play III

Policymakers & Public Sector Actors

Play I

Play II

Play III

Private Sector

Play I

Play II

Play III

Technologists

Play I

Play II

Play III

Funders

Play I

Play II

Play II

Urban Governance

Stewards / Steward-like Initiatives

Play I

Play II

Play III

Policymakers & Public Sector Actors

Play I

Play II

Play III

Private Sector

Play I

Play II

Play III

Technologists

Play I

Play II

Play III

Funders

Play I

Introduction

In the current data economy, the ability for individuals and communities to participate seems to be both narrowly defined and limited in application. This situation is further complicated by varying expressions of digital rights across jurisdictions and conceptualizations of where individuals fit into the vast patchwork of data fiduciaries, intermediaries and regulators.

At an individual level, most of us are familiar with exercising ‘choice’ in the data economy through the provision of consent – a process that has been criticized as broken and not extensive enough. Moreover, the role of individuals and communities – the primary producers of data – are largely rendered invisible, affording limited control over the use of their data by public agencies and private entities alike.

However, it is important to acknowledge that there is collective societal value that can be unlocked with data, and central to this unlocking is the meaningful participation of individuals and communities in data governance, in a way that goes beyond notice and consent mechanisms. Yet, several barriers impede how participation can be defined, incentivized and scaled in the broader stewardship ecosystem.

Solving for these issues requires both an acknowledgement that current systems effectively stymie substantive participation and a deeper investigation of what practices can be drawn from historical and contemporary modes of community mobilisation to define new conceptions, modalities and pathways for participation.

What can participation look like in the data economy and what existing literature and use cases demonstrate a promising path forward?

Participation – a foundational pillar of data stewardship

This course of inquiry finds resonance in the evolving discourse around data stewardship which pushes for a more agential and equitable approach to participating in the data economy. It imagines a more just ecosystem that enables individuals and communities to exercise their data rights in accordance with their respective data priorities while ensuring necessary safeguards are in place for the protection of their privacy as well as rights over their data.

Data stewardship’s participatory ethics finds its genesis in Elinor Ostrom’s design principles for community-led governance of commons – which presents a third avenue that exists beyond the state and private sector – to effectively manage the utilisation of resources at the level of communities. This framework has also been historically reflected in the governance of common resources including the management of ecological services and pooled goods like the oceans and atmosphere. A significant artifice of her work is the relational nature of common pool resources, highlighting the interconnectedness of the commons, communities and livelihoods that determine how resources are governed and how members of the community participate in such governance processes.

Participatory data stewardship similarly furnishes a spectrum of participation for communities to be involved in the use of

their data. It can help ensure that communities are involved in decision-making processes throughout the lifecycle of data – from its collection through to its processing, storage and sharing to eventual deletion. Sherry Arnstein’s ‘ladder of citizen participation’, can be used to diagnose the current data governance practices as low levels of participation, and point towards the many possibilities data stewardship provides to enhance participation. This framework adapted by the Ada Lovelace Institute for data stewardship, illustrated in the figure below, surfaces a useful starting point for community participation in data stewardship. Participatory data stewardship similarly furnishes a spectrum of participation for communities to be involved in the use of their data. It can help ensure that communities are involved in decision-making processes throughout the lifecycle of data – from its collection through to its processing, storage and sharing to eventual deletion. Sherry Arnstein’s ‘ladder of citizen participation’, can be used to diagnose the current data governance practices as low levels of participation, and point towards the many possibilities data stewardship provides to enhance participation. This framework is adapted by the Ada Lovelace Institute for data stewardship as well, illustrated in the figure below, surfaces a useful starting point for community participation in data stewardship.

Environment & Sustainability

Climate change has profoundly impacted the health of the planet, threatening the loss of biodiversity and irreversible harm to the air and oceans – all common resources. The crisis has been further exacerbated by limited and poor understanding of data which has in turn obscured the understanding of human impact on the climate and the vulnerabilities it produces for marginalised communities. For instance, the Koli community, a traditional small-scale fishing community in Mumbai, have pointed towards a lack of substantive traditional ecological knowledge in guiding climate mitigation policies. This community is not only disproportionately impacted by climate risks resulting in shrinking fish catches, but their livelihoods are also threatened by development/infrastructure projects.

In order to understand the impact of climate change on marginalised communities, it is necessary to have environmental data which is inclusive of substantive traditional knowledge. Environmental data has become central to bottom-up movements which prioritise the participation of local communities in development initiatives and enables them to set their own goals. Advancement in data analysis and data gathering technologies have also expanded the potential of collection and sharing of environmental data. Tools developed such as Mapeo (developed by organisations Digital Democracy) have been useful in the collection and sharing of environmental data and building biodiversity science that is informed by bottom-up community knowledge and involvement.

Though promising, tools like these are exceptions within a data economy where ultimate control over data is largely concentrated by state and private actors – often with minimal accountability – increasing the scope for misuse. Weaponization or manipulation of environmental data has systematically undermined conservation efforts as well as the rights of indigenous communities. The actions of the WHO in deleting India’s air pollution data from its portal is one such instance where data misuse has stymied transparency and climate mitigation efforts.

Challenges with accessing environmental data & consequent impact

It is often the least well-resourced actors who stand to suffer most from climate change (with actors in the Global South being particularly vulnerable). This is further exacerbated by digital transformation-related solutions which may deepen inequities. Increasingly, it is becoming evident that the loss of agency around data and information that relates to common pool resources (such as water bodies and forests) can have a knockon effect around conservation efforts and is also beginning to impact the livelihood of marginalized communities.

At the core of this exists a fundamental challenge in the management of public resources. The current state of overexploitation – resulting in a pillage of the commons – stands opposed to the long-standing traditions of natural preservation and a delicate ecological equilibrium which indigenous communities have successfully maintained. Prioritising a return to community-oriented modes for governance of natural resources will be necessary, given that ongoing digitisation processes threaten to amplify existing environmental injustices.

Mainstream environmental policies and interventions have also failed to acknowledge the unique role indigenous communities can play in stewarding the earth’s natural resources. Studies have shown that community led protection of diversity results in better conservation of the environment. The Namibian government recognised community-based natural resource management of 82 conservancies covering about 20% of the country’s surface. These initiatives resulted in improved living conditions of local communities while also restoring animal populations. However, it is also important to note that it is now indigenous and marginalised communities who face the greatest degree of impact of climate risks – and bear the brunt of an ever increasing burden of pollution. The added burden that may be imposed by stewarding these resources today must be matched with adequate support from the entities responsible for pollution.

Relatedly, technocratic decisions, the enforcement of which is entrusted unto experts and bureaucrats, are often at odds with the decision-making processes within local communities. This reflects quite clearly in the impact of digitisation of land records under the Bhoomi program in Bangalore, where as a consequence of this program, corruption increased and relatedly so did costs for farmers. Instead, the e-governance scheme enabled efficient corporate capture of land for developers and prioritised the interests of IT companies.

Existing pathways to environmental justice that can inform participatory and community-oriented governance

Elinor Ostrom’s work demonstrates how communities can forge a framework to govern their common resources in a mutually beneficial and sustainable manner. Ostrom draws from a rich history of community-initiatives and organisations which have driven development efforts in aid of natural resource management. One such initiative is the incorporation of the concept of ‘buen vivir’ undertaken by some Latin American countries. Buen vivir is based on the belief that true well-being is only possible as part of a community. Buen vivir began to grow in popularity in Latin America in response to depletion of natural resources, climate change and the necessity of developing an alternative to a model of economic development informed primarily by the experience of the Global North.

Similarly, the Maine Lobster Fishery is credited for its steady yield and sustainable growth for many decades due to the lobster fishers’ community who monitor their livelihoods through an informal process of control, mutually negotiated rules for resource extraction and territorial governance. Elsewhere, the Gond Tribe in Mendha in the district of Maharashtra has been recognized for its movement towards self-rule and forest conservation. One of the most significant actions that the villagers took was declaring the land in the village as village commons under India’s Forest Rights Act, 2006. Considered an empirical experiment, Mendha Lekha has since demonstrated a positive ecological impact on its village ecosystem and economy that is guided by a participatory resource governance system, ethics of consensus and inclusion.

Building on Ostrom’s work, Frischmann developed the Knowledge Commons framework specifically tailored to the properties that distinguish knowledge from natural resources. The framework refers to knowledge as a broad set of intellectual and cultural resources which includes group information, science, knowledge, creative works and data. Frischmann’s framework puts special emphasis on managing rival resources within a knowledge common since shared resources may not be fully independent to other resources. This flexibility within the knowledge commons approach has the advantage of encompassing a wider range of interests than a private right.

Knowledge commons have existed and continue to in various countries. Indigenous communities within Australia, Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia have developed a database including information like recording animal and plant behaviour to historical observations on biological or physical factors in climate events. This database follows strict guidelines on ability to be operated smoothly in environments with limited technical expertise, ease of use, free and open source software, respecting cultural sensitivities, portability and sustainability. This approach on commons has many lessons for data, especially as we begin to think of it as a collective/community resource and not just an individual one.

The role of stewardship in institutionalising community-governance over resources and related data/information

Discourse on environmental stewardship and biocultural rights are also closely tied to environmental justice and collective governance. These can be similarly drawn from while building blueprints to translate stewardship into action in the environmental domain.

This requires recognizing the degree to which vulnerable and marginalised communities are disproportionately affected by climate risks. The tenets of the environmental justice movement embed ethics of procedural and distributive justice alongside a recognition of communities’ rights to self-determination. These principles find resonance within contemporary discourse on data justice. For instance, Taylor’s framework for data justice is based on three pillars: visibility, digital (dis)engagement and countering data-driven discrimination. The first pillar deals with both privacy and representation. The second pillar deals with freedom to control the terms of one’s engagement with data markets focussed on potential benefits to low-income communities. The third pillar is power to identify and challenge bias in data use and freedom to not be discriminated against.

Building on data justice work and proposing solutions on social asymmetries and injustice, data stewardship has been proposed as a solution to monitoring data, inclusion of marginalised communities, contextualising tech-based solutions and tackling climate change. Data stewardship will be relevant to climate-related goals and for sharing technical knowledge and information with decision makers and stakeholders locally, regionally and globally.

Stewardship can be imagined and implemented in a variety of forms – one thread of this development is focused on indigenous data sovereignty. Indigenous data sovereignty (IDS) has been defined as “indigenous people’s rights to control data from and about their communities and lands, articulating both individual and collective rights to data access and privacy.” Some projects aiming to improve environmental stewardship have embraced IDS principles. For example, in Canada, the Arctic Eider Society is developing a platform to study ice-monitoring which is conceived as an instrument to empower indigenous self-determination. The platform’s privacy features include an option to assign indigenous stewardship to user content, giving granular data access to specific communities, regional, and other affiliated local organisations.

These various bodies of research and practice around the community and collective governance of resources are necessary to continue unravelling. They provide significant grounding for designing pathways for greater control and participation in data decision-making for indigenous communities. Similarly, it may help situate the role, responsibilities and related requirements data stewards may have for empowering indigenous people in their digital lives.

Considering existing discourse and our learnings on stewardship, we believe that the environment sector is ripe for collective action on data through models of stewardship. Therefore, this playbook provides a set of emerging strategies for stakeholders to help address challenges that emerge from enacting stewardship in the environment sector.

Healthcare

Data-driven innovation bears immense potential to fundamentally transform healthcare, expanding the scope for precision treatment, research and drug development as well as effective and timely public health surveillance. Such innovation constituted the heart of public response to the pandemic – from using data to guide healthcare policy decisions, support isolation and contact tracing, track infection and disease incidence to fast-track vaccine formulations.

Specifically, health data governance refers to the management and oversight of the collection, storage, use, and sharing of health-related information. It plays a crucial role in ensuring that patient rights, public health benefits, and ethical considerations are respected and upheld. The governance of health data must balance the need to protect patients’ privacy and confidentiality while opening up the use of data for further research. The overarching aim of health data governance is essential for maintaining the trust of patients and the public while also advancing medical research and public health outcomes.

Patient rights over health data

The first generation of health data regulations sought to prevent harms from data misuse and made individual patients the node of their frameworks. This includes the emergence of legislations such as the the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, 1996 (HIPAA), the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, 2004 and the host of provincial health regulations it spawned across Canada, as well as data protection legislations such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, 2018, Kenya and Ghana’s Data Protection Acts, among others.

However, such an individualistic approach to health data regulation, one that is essentially anchored in consent provisioning, is manifestly inadequate against a backdrop of growing digitisation of health services. For one, scholars have drawn attention to the limits of individual privacy self management that prevent patients from providing informed consent and exercising meaningful control over downstream uses of their health data. Two, the emergence of big data analytics and the application of newer technologies such as artificial intelligence to health information processing has rendered mass aggregation of datasets plausible, widening the power asymmetry between patients and data processing entities. Third, aggregation lends itself to data processing that can manifest as collective harms, necessitating newer conceptions of data rights that inscribe elements of collective governance within frameworks for health data regulation.

With the evolution of data privacy and protection legislations globally, there is a pronounced need to embed provisions for collective governance and oversight of health data use by providers, private entities such as pharmaceutical companies and public bodies that process health data. Solidarity-based systems for data governance offer a new pathway to reimagine health data regulation towards plural futures that are sensitive to ethics of community participation and fair distribution of collective benefits from health data use. This renewed conception of health data regulation that can push for and build on partnerships amongst various stakeholders in the healthcare ecosystem – patients, providers, researchers and policymakers – to ensure that health data is leveraged responsibly and founded in respect for patients’ rights.

Public health priorities

Public health institutions steward vast troves of health data (ex: census data, national health surveys) that when safely unlocked can inform myriad policy decisions and medical research. However, the ability to process this health information hinges on granting access to third parties that may include a variety of stakeholders such as academia, non-profit organisations and private companies. Such data sharing agreements are seldom straightforward, often producing contentious trade offs that undermine trust in public institutions to deliver fair and equitable health outcomes to patients at large.

There exist several documented examples of contentious data sharing arrangements that produced mass public outrage, forcing governments to either altogether reconsider their proposals or seek refuge in questionable legal exemptions during health exigencies. Successive NHS data sharing agreements with private companies like DeepMind, Palantir and Amazon constitute instances of data sharing by public health agencies that were censured widely. Elsewhere, the COVID-19 pandemic morphed into a hotbed of rampant privacy violations wherein governments circumvented legislations to implement mass contact-tracing with overbroad provisions to collect citizens’ data, as demonstrated through India’s Arogya Setu and Singapore’s TraceTogether applications.

While it is undeniable that data sharing by public agencies can advance collective health outcomes, it is also fraught with concerns around patient privacy and regulatory ambiguity. Thus it is imperative to conceive of mechanisms that open data collected by public health institutions in ways that enhance social welfare without undermining trust and patient rights over data. Frameworks for attaining social licences – informal systems of allowances and permissions granted to public authorities and corporations to perform activities that generate public value – can help reimagine health data sharing agreements that manifestly privilege social welfare. Specifically, scholars characterise three elements, in the context of health data sharing for COVID-19 surveillance, that are critical to achieve trustworthiness and hence, social licence for public action – compliance with data privacy legislations, adhere to transparency through forward looking data governance rules, and continuous commitment to public involvement throughout the lifecycle of data use.

In foregrounding transparency and public participation as crucial artefacts, regimes of social licensing help enhance community trust and legitimacy for processes of health data sharing. As also, social licensing surfaces an alternative normative blueprint to reconstitute power relationships between individual patients and patient groups on the one hand, and public health authorities that continue to collect and amass valuable data that can produce sound policy decisions.

Ethics of monetising health data

Monetisation of health data has been touted as the next frontier of innovation within digitised health systems, with corporations and scholars alike calling for formulating frameworks of data ownership that can be accorded to individuals. Ownership herein refers to an approach to data regulation, particularly health data, with its genesis in the political economy of property rights. An analogous regime for data would imply that individuals have “ownership” over their data that is not dissimilar to owning property such as land, houses, etc. While the approach may seem intuitive and compelling, it is riddled with myriad conceptual and ethical quandaries.

For one, data is not a static economic resource that can be valued precisely and traded in exchange for money or services. In contrast, scholars have drawn attention to the dynamic, nonrivalrous and relational nature of data that lends itself to use and re-use by a variety of data users and custodians, even after individuals and communities have parted with said data. Second, ownership approaches to data regulation risk commodifying privacy in ways that are untenable with contemporary human rights jurisprudence that has come to regard privacy as an inalienable right. Alternatively, a decisional autonomy conception of data regulation – one in which individuals and communities are accorded a regime of rights to lay claims over their data – is preferred inasmuch as it recognises the role of individuals and communities in data production, creating pathways for their engagement in data governance decisions.

Lastly, data monetisation in the context of healthcare carries with it risks of creating unfair dependencies on income earned by selling data, exacerbation of income inequities, reduced accuracy of datasets and lastly, waning altruistic data sharing for public benefit. Further, prevailing logics of Big Data demonstrate that data and knowledge production occur at a societal level, producing both collective benefits and harms. In such a context, it is ill-advised to offer data monetisation as an incentive to individuals when they are impacted by their own data as well as that of others in ways that possibly magnify discrimination and bias. Instead, policymakers would benefit from recognizing the limits of existing individualised data protection legislations and move towards a conceptual framework for data governance that focalises collective privacy and data rights as the foundation for future regulation.

Role of data stewardship in health data governance

Given these risks, data stewardship presents an optimal vehicle to realise the underlying need for holistic frameworks of patient rights and, more broadly, the need for community participation in health data governance. Our research on various modes of community-oriented data governance, and bottom-up models like data stewardship has presented healthcare as not only a priority sector, but one with significant room for public engagement.

Stewards and steward-like initiatives often function as conduits to build trust, and provide communities a degree of collective leverage. In public health policy making, bolstering community engagement and trust is essential to work toward social licensing regimes. In the context of data monetisation, stewardship can help realise data rights in a meaningful manner, acting as a community-centric accountability layer as well as including individuals and groups in defining value generation and distribution. This presents great potential to avoid unfair practices and harms like exclusion, bias and the perpetuation of legacy inequalities.

We have highlighted key challenges that plague the instantiation of meaningful participation in health data governance and patient rights. Based on numerous global case studies, we find that for each stakeholder in this interconnected ecosystem, there are valuable strategies and strengths that situate data stewardship as an institutional framework: one that can have many forms, but ultimately creates a site to anchor these concerns and contemplate renewed approaches to health data governance.

Urban Governance

While information has always played an integral role in urban governance, rapid advancements in digital technologies and computation have spurred a transformation in urban governance. New and emerging technologies, catalysed by the availability of large volumes of data are enabling the rapid digitisation and innovation in the domain of urban governance, which can be understood as the “many ways in which individuals and institutions, both public and private, plan and manage the common affairs of the city”.

Data innovations and new models of reconciling diverse forms of information have been the cornerstone of these transformation efforts. These approaches range from the creation of ‘digital twins’ for cities, a virtual model designed to accurately reflect a physical object, building collaborative and open digital platforms that afford easy integration with services, or supporting ecosystems that foster innovation around specific use-cases like mobility as a service. Governments are now invested in leveraging data to shape accessible, people-centric, sustainable ‘smart cities’. These efforts have transformed the governance of urban spaces and cemented the criticality of data to urban governance.

However, much like most other sectors witnessing a digital transformation, ultimate control over the data lifecycle – from collection to processing – is largely concentrated by state and private actors. In addition to this, processes of decision making based on this data are also exclusionary, leading to decisions that are not always aligned to the on-ground needs of communities. Despite urban governance being an area where the daily lived experiences of people are most directly impacted, there exists little visibility, agency and participation for communities.

Urban data governance to address legacy inequalities

Numerous studies have highlighted systemic inequities across the world in the design of urban spaces and allocation and quality of resources. Areas populated by marginalised communities tend to have poorer quality of basic resources, be it air, water or roads. Moreover, investment in public spaces in such areas is typically lower, and connectivity between these areas and central business districts is also more problematic.

Access to quality housing in urban spaces is also predicated on historical inequities, with housing crises being more of a result of unequal distribution of resources, rather than a complete scarcity of them. In the digital sphere, some jurisdictions have also reported areas with marginalised populations being quoted higher prices for basic digital infrastructure such as internet connectivity. In a highly digitised world, this has knock-on effects on matters from education to finding new jobs.

Historical inequities in urban design also typically put a higher burden on marginalised communities. People from marginalised communities typically spend more time commuting to their places of work, which affects their health and wellbeing. In the United States, neighbourhoods with a predominance of blackowned businesses also received less benefits from relief efforts on average.

Urban data governance presents an opportunity to address these existing, systemic inequities. By leveraging the power of data, urban spaces can be better designed to rebalance the issues caused due to systemic problems. Significantly, in addition to retroactively addressing inequities, data-enabled insights can also be used to proactively build new systems that rebalance and democratise urban spaces.

Redefining the centrality of the State

Historically, the State has typically stewarded urban areas, as the primary builder and holder of urban spaces – be it through municipal authorities or public utility corporations. Resultantly, urban spaces have been designed largely in accordance with the dictates of the State, with communities’ participation limited more to submitting proposals and providing comments and feedback on public efforts and policies.

The integration of data into decision making for more informed urban governance provides an opportunity to reframe this paradigm. Crucially, data promises greater buy-in and participation for citizens and communities in the governance of their urban spaces – giving them a greater say in how the governance of cities can be reflective of their needs and concerns. This greater involvement and agency of communities in data-enabled urban governance runs across the entire cycle of governance – from data collection to planning to implementation.

This theoretical promise however has not adequately translated into practice. Despite many smart city endeavours attempting to embed participation into the design and implementation of their processes, community participation in urban governance continues to be broken and insufficient. The State continues to dominate the stewarding of urban areas, with data sources that inform decision making, still largely lying in the domain of public sector data or private industry data.

The centrality of community interest to urban data governance

Non-personal data plays the foremost role in urban data governance. This non-personal data can be both personaladjacent, in that it is aggregated and anonymised personal data, as well as data not tied to personal data at all – data about water or air quality, for example. Regardless of the linkages to personal data, almost all data used for urban governance is closely related to communities in terms of the direct, vast impact it has on their lived experiences and the insights it provides about them. Analysis of air quality data from three major cities in Canada (Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver) showed that indigenous, low-income and immigrant residents are exposed to higher cumulative air pollution. Similarly, studies in the US, Asia and Africa, revealed that communities with lower socioeconomic status faced higher levels of air pollution. Likewise, mobility data can provide important insights into trends on preferred modes of transportation, movement timings and movement patterns – all linked to communities.

Despite the availability of such data and insights from it, communities typically do not have access to such data or even have a say in the collection of the same. This can have a direct impact on a community’s ability to push for urban policies that can address issues surfaced by this data. On the flip side, exclusion of communities from the data gathering stage can also invisibilise communities and the issues they face at a policy making stage. It therefore becomes crucial to recognise the interest of communities in data that is reflective of / linked to them.

Data stewardship as a means of fostering participatory urban data governance

Frameworks for data sharing should be citizen-centric, enabling them to have greater control over data collection and sharing processes. While data enabled urban governance has immense potential, there are several barriers that impede this process. In addition to the lack of community participation in the process there are also issues of data being held in private silos, a lack of technical standards, and privacy concerns from data sharing.

Typically, in conjunction with smart city initiatives, several governments have adopted open data platforms and published open datasets. This is seen as an increasingly attractive datasharing model which, though meriting encouragement, is limited in scope. Yu and Robinson (2012) argue that open government and open data cannot be conflated and that often the success of open data initiatives is dependent on the consistency of public policies that may shift according to the whims of administrations. Also, as these are government-led, there are no guarantees of the quality or accuracy of the data shared.

While some of these open data-sharing initiatives are designed to be collaborative and engage stakeholders and data-users throughout the process, other models do not take into account the usability of the data released. There is also a lack of trust between the various stakeholders involved in urban data governance. Without collaboration with these players and access Frameworks for data sharing should be citizen-centric, enabling them to have greater control over data collection and sharing processes. While data enabled urban governance has immense potential, there are several barriers that impede this process. In addition to the lack of community participation in the process there are also issues of data being held in private silos, a lack of technical standards, and privacy concerns from data sharing.

Typically, in conjunction with smart city initiatives, several governments have adopted open data platforms and published open datasets. This is seen as an increasingly attractive datasharing model which, though meriting encouragement, is limited in scope. Yu and Robinson (2012) argue that open government and open data cannot be conflated and that often the success of open data initiatives is dependent on the consistency of public policies that may shift according to the whims of administrations. Also, as these are government-led, there are no guarantees of the quality or accuracy of the data shared.

The past few years have witnessed numerous instantiations of stewardship like initiatives. Urban Living Labs, for example, have emerged in many geographies as co-creative spaces to reconcile stakeholder groups and act as hubs for participatory processes to be built and deployed in real time. Additionally, multilateral and international institutions like the United Nations Development Programme are also supporting joint policy experimentation initiatives – Pulse Labs in Jakarta’s and Pintig Lab in the Philippines are two such examples. There has also been buy-in from public sector entities, with efforts such as DECODE (piloted in Amsterdam and Barcelona), Adelaide’s Smart City Studio, and the Houston Hackathon all exploring different modalities of involving communities more intimately in urban data governance.

Stewardship efforts, and more broadly stewardship as a concept, in the urban governance space remain relatively esoteric and face numerous challenges. This sectoral pull-out provides a set of emerging strategies for stakeholders to help address challenges to fostering data stewardship in the urban governance sector.