Context

The impact of climate change on society has become more visible, compromising infrastructure, livelihoods, food security, and health. These issues are exacerbated for communities in the Global South. As communities envisage and attempt to respond to these challenges, we stand at a critical juncture in how we imagine—and at times reimagine—approaches and design interventions.

In addressing the impact of climate change, we have to be cognizant of how communities are being affected by, and adapting and responding to the shifting climate patterns. The different strategies and knowledge systems they rely on to adapt and mitigate the effects of climate change become pivotal to creating context-specific interventions.

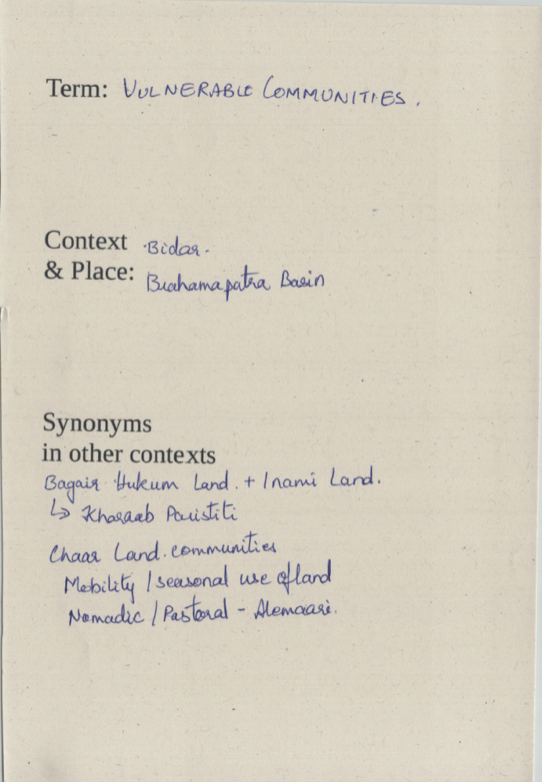

As part of a research project examining bottom-up data initiatives for climate action, Aapti Institute, in partnership with Data2X, is attempting to uncover the nuances involved in building and implementing these data initiatives and the implications of such initiatives on communities spearheading hyperlocal climate action. A series of case studies that emerged as part of this project revealed the importance of community knowledge and community networks in creating, preserving and sustaining climate resilient livelihoods, and simultaneously raised questions on how these can be governed effectively through data governance principles. Ongoing work under the Climate Resource Center by Aruvu Collaboratory, the Living Labs Network & Forum and TeamYUVAA with the farmers in and around Bidar revealed a diverse and rich range of lived experiences of reading, anticipating and adapting to climate shifts. The lived experiences we are documenting in this engagement also highlight the multiple ways the labours of climate shift anticipation and mitigation is situated and intertwined with the particularities of a place.

What does it mean to bring the situated knowledge of the communities to inform global climate action frameworks? Integrating communities’ lived experiences, practices, and situated knowledge requires us to rethink global ideas of data-driven climate change response and mitigation. Thinking through such approaches of ‘community technology’—weaving together community-driven approaches to the prevailing systems and knowledge infrastructures—can help root our responses in fairness, equity, and accessibility as we tackle questions surrounding data ownership and governance. At the same time, understanding the lived experiences of communities through place-based, participatory approaches is a crucial link to assessing how data systems can be designed to return value to communities stewarding natural resources.

Aapti Institute is attempting to build a network of community organisations, researchers and domain experts to engage with these questions in greater depth, as part of which a series of network convenings are being hosted. In the second of the series of convenings, Aapti Institute collaborated with Aruvu Collaboratory and Living Labs Network & Forum on a day-long workshop on ‘Building Community Tech for Climate Action’.

Objectives

Through this workshop, we aimed to engage in discussions on community technology for natural resource governance, through centering the ongoing efforts of Landstack, Land Conflict Watch, Living Labs Network & Forum, Team YUVAA, Dakshin Foundation, and WRI India. We frame community technology as technologies rooted in communities’ lived histories and practices of sensing and responding to climate change. Making such technologies visible and exploring possibilities of centering them in the global frameworks of data-driven climate change response, we believe will enable more contextually relevant and effective, inclusive climate change initiatives. Community technology can be pivotal to finding new ways to advocate and deliver climate change-linked programmes.

Driven through learning cases and sessions of collaborative and critical making, we engaged attendees on key aspects as follows:

- Identifying the roles that grass-roots communities can play in the climate data dialogue

- Navigating critical data questions in climate action, centring fairness and equity

- Weaving together a systems approach focusing on climate data to community-driven climate action

- Collaborating on ideas on the governance principles for community-tech

- Broadening the reach of Aapti Institute’s network for research on bottom-up climate data

Themes

The workshop was organised into three thematic areas, chosen based on the prevalence of data initiatives in these areas, as well as their importance in the global climate dialogue:

- Climate and agriculture, and land use.

- Climate and water-based livelihoods.

- Climate and urban mobility.

Across these three thematic areas, we explored the following key questions:

- How can hyper-local data and bottom-up approaches strengthen natural resource management?

- How can data-driven initiatives help in scaling sustainability and climate action?

We explored different facets within the three thematic areas through synthesized learning cases from the works of the following organisations:

- Land Conflict Watch explores land, climate change, and natural resource disputes in the country through a multi-disciplinary approach to facilitate better decision-making regarding investments and governance. They have successfully built the country’s first and only database of ongoing land and resource conflicts as well.

- Landstack works on building an informed land ecosystem that expands land governance space, synergises land interactions and catalyses land stewardship for improved land relations and outcomes—bridging existing gaps in land governance, expanding the space for land-related initiatives and strengthening relevant institutions and actors.

- Climate Resource Center at Living Labs Network & Forum, in collaboration with Team YUVAA is a socio-technical platform for farmers, their families and allies, where experiences, practices and responses within agricultural practices are documented, disseminated and developed through local collaborative action research.

- Dakshin Foundation aims to catalyse conservation and natural resource management, while promoting and supporting sustainable livelihoods, social development and environmental justice. By strengthening networks at local and national levels and supporting advocacy campaigns, Dakshin works to build grassroots capacities to secure ecosystems and rights and engage in—ecologically and socially appropriate—conservation and environmental decision-making in India’s coastal, marine and mountain ecosystems.

- World Resources Institute – India focuses on data-driven climate action and a multi-stakeholder approach, collaborating with public institutions for urban governance and vulnerable communities on building climate-resilient policies and infrastructure, helps participants better understand the climate infrastructure.

Methodology

The workshop was driven by three interlinked activities: Gallery walk, Collaborative making prompted by learning cases, and culminating in a panel discussion.

The day began with the collaborating organisations sharing the context of their work through presentations, followed by a gallery walk where we displayed curated works from the collaborating organisations in the three thematic sections. The learning cases, visual posters and reports offered more context on conversations on climate action. The participants engaged with each of the themes, having informal and specific conversations with the members of the organisations and the co-facilitators.

The learning cases were put together by the co-facilitators from Aapti and Aruvu in conversation with the collaborating organisations, with the intent to bring forward the diversity and uniqueness of the lived experiences and situated knowledge held by the communities that the organisations closely worked with. While highlighting the lived experiences the learning cases posed prompts for the participants to engage with. After the gallery walk, the participants grouped into themes and read the respective learning cases together, annotating and creating a session of critical making structured along the prompts raised by the learning cases. The conversation enabled the participants to express their responses to the prompts through the act of making an artifact together. The activity of making was driven by a clear idea of an output: an Alternative Glossary of Climate Terms, System & Actor Map, and an Imagined Map of Urban Mobility Infrastructure. The focus on the output brought together people and gave space for all participants to actively share their responses to the prompts, as well as respond to each other’s thoughts and ideas while being engaged in the activity of making. In this sense the artifacts held the conversations literally; all the conversations were written down as tags and annotations by the group members, and they hold the nuanced collective understanding and possible directions forward discussed by the respective groups.

Bringing together a diverse set of stakeholders, community members, grassroots workers, academics, and practitioners, we aimed to create a shared understanding of data-driven practices for climate action. Rooting our conversations in lived experiences of climate change as highlighted by the learning cases, the working sessions created learning space to further our understanding of the systems and the role of different stakeholders in facilitating and sustaining community-driven action.

Working Sessions and Outcomes

Agriculture and Land use

This learning case was brought together from the work of the Climate Resource Centre (CRC), Land Conflict Watch and Landstack. The learning case studies were built upon Land Conflict Watch’s reportage on land grabbing for renewable energy in Maharashtra, the Climate Resource Centre’s case study of Veerbushan’s natural farming practice in Bidar and Landstack’s insights on Community Forest Rights management in the North East and Odisha. Excerpts from conversations and learnings were narrated together along with discussion prompts that emerged from that section.The learning case study highlighted the need for common vocabularies, encouraged plural and multi-perspective understandings of phenomena that communities experience and researchers study. There were three discussion prompts in the learning case that prompted critical thought while making the vocabulary:

- “Greener energy for the greater good” uses certain terms as ideals to guide climate adaptation efforts. However, it often opens up communities to unintended vulnerabilities. Where do the ideas come from? Do they offer holistic benefits to the communities?

- Existing climate and land regulation terms do not represent communities’ relationship to the land. How does the making of locally relevant and understood dictionaries affect the making of policy, law?

- How do communities perceive changes in land, climate and outcomes? How different are their metrics from our notions of documenting changing climates? How do they drive climate action?

Mahmodul Hassan reporting for Land Conflict Watch writes of land grabbing from small farmers by solar power companies in Maharashtra’s Jalgaon district. The report of communities being vulnerable to such large renewable energy projects illustrated the state of land regulation in regard to forests, agricultural land and renewable energy promotion. It also presents the nature of regulation that is not legible to communities, especially new regulation that makes them more vulnerable to coerced involvement.

For this case, the CRC brought in excerpts from a case study of Veerbhushan’s farming practice in Bidar. Veerbushan was also present with us for the working sessions. Veerbushan has been practicing natural farming for over four decades. Veerbushan comments on the problem and solution approach we take in tackling climate change: “Yes, today everyone talks about problems in agriculture. Some people like you talk about climate change, but the system needs to be changed. Today’s’ attempts are to find our culture, ತಪ್ಪು ದಾರಿ ಸರಿ ಪಡಿಸುವುದು ಇವತ್ತಿನ ಕೃಷಿ (To mend the wrong ways is today’s agriculture). Nature will reward us once we start looking back and ensure that we co-exist within its cycle”.

We draw from Landstack’s work in the North East and Odisha in understanding Community Stewarded forest management. In Odisha and Bidar, communities closely attuned to the seasonal rhythms of the land observe cultural festivals before harvesting, aligning their practices with nature’s cycles. In Odisha, the Baa Parba Puja, a spring festival, signals the start of collecting Mahua (Madhuca indica) and Sal (Shorea robusta) flowers, marking the harvest period. These relationships and understandings of land, climate and changes do not match with top-down ways of classifying, governing and communicating.

Globally, agricultural data is perceived as critical to decision-making in food systems. Digital Public Infrastructure are positioned as pathways to boost efficiency and inter-stakeholder collaboration; there is limited scope for communities to actively participate as decision-makers, leaving scope for extractive practices with no return of value to these communities, and undervaluing the wealth of knowledge generationally held by them. There is a gap in research communication and policy implementation and grass-roots action, in understanding hyperlocal manifestations of climate change by the communities living closest to the effects, which the learning case highlights.

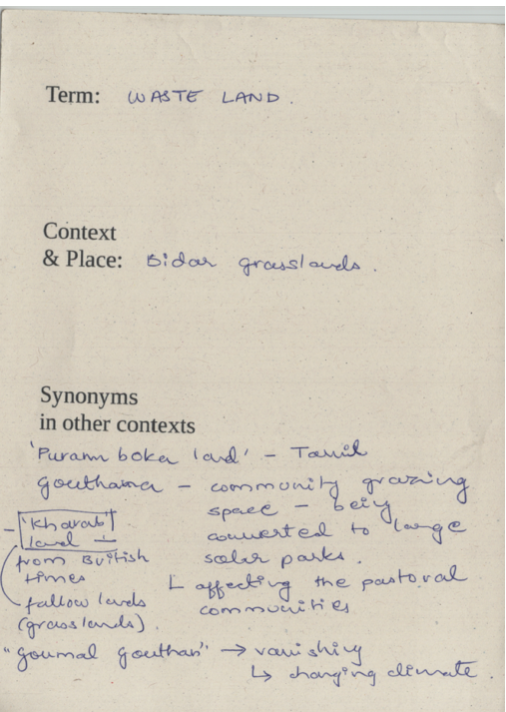

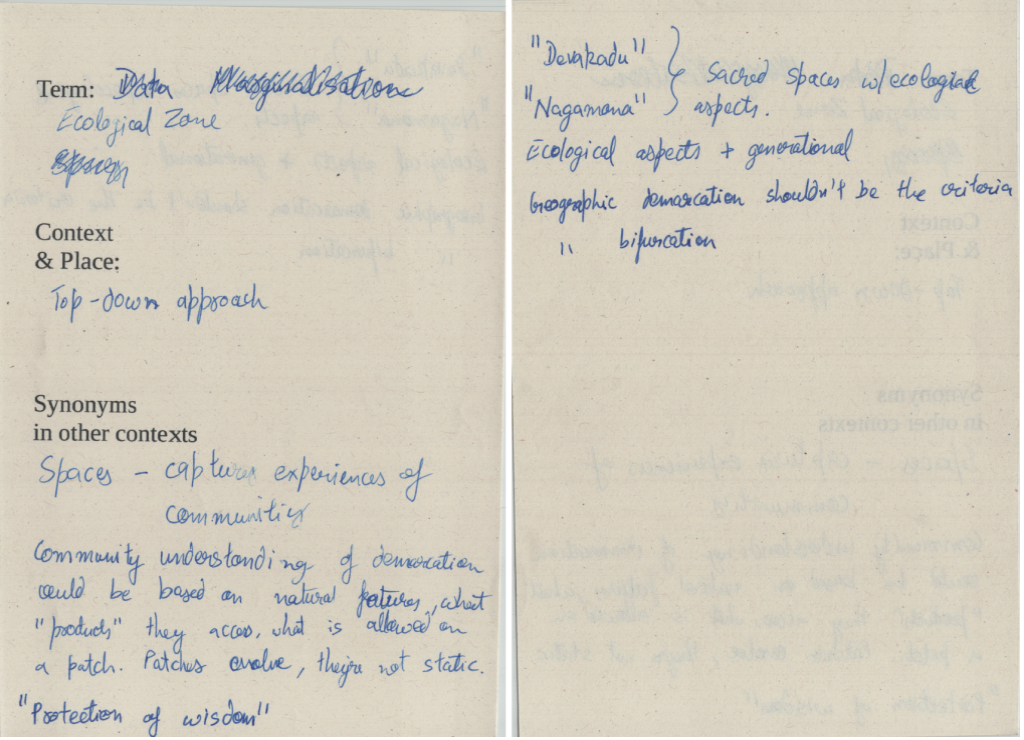

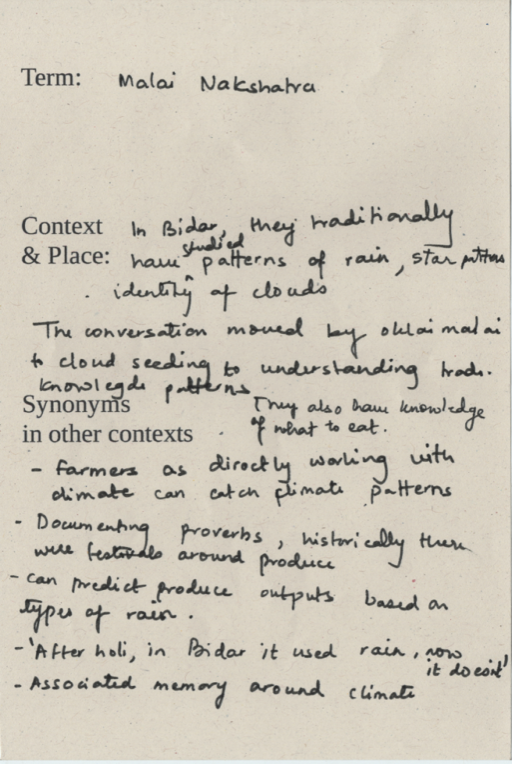

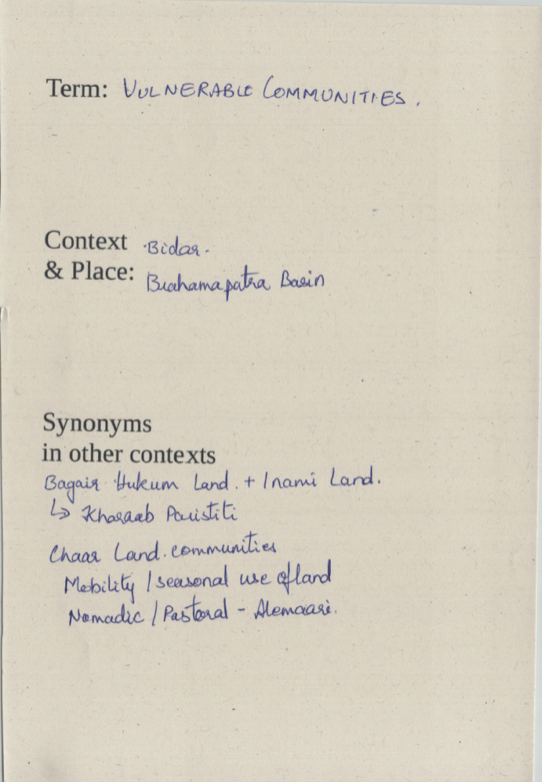

To explore the possibilities of bridging this gap, the working session involved the critical making of an Alternative Vocabulary of Climate Terms and Phenomena. We highlighted terms, phrases and phenomena from the learning case and then, along with participants and community members and grass-roots activists, namely, Veerbushan Nandgaon, Harshawardhan Rathod and Vinay Malge, we renarrated those terms and phenomena in the context of Bidar as well as the contexts of the participants who were curious about renarrating in their own languages, as depicted by the vocabulary cards.

The Alternative Vocabulary moves away from the notion of communities being subjects of conventional climate research and recognises them as knowledge-producers who organise to innovate and take action.

Water based livelihoods

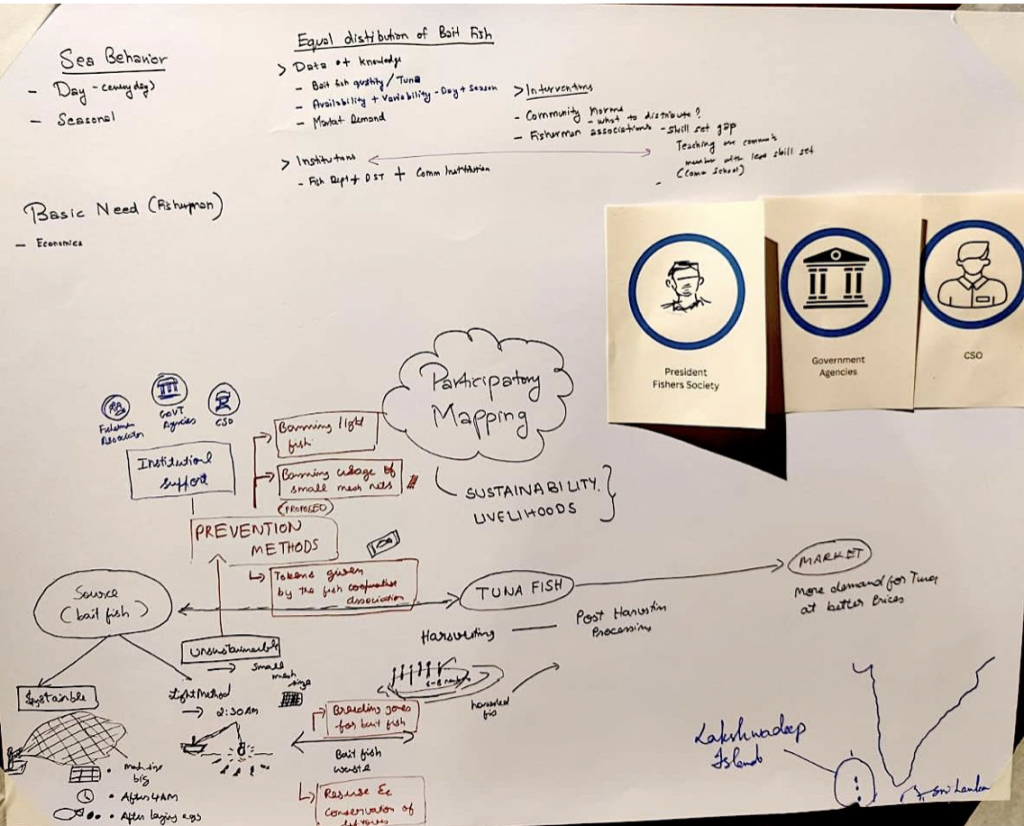

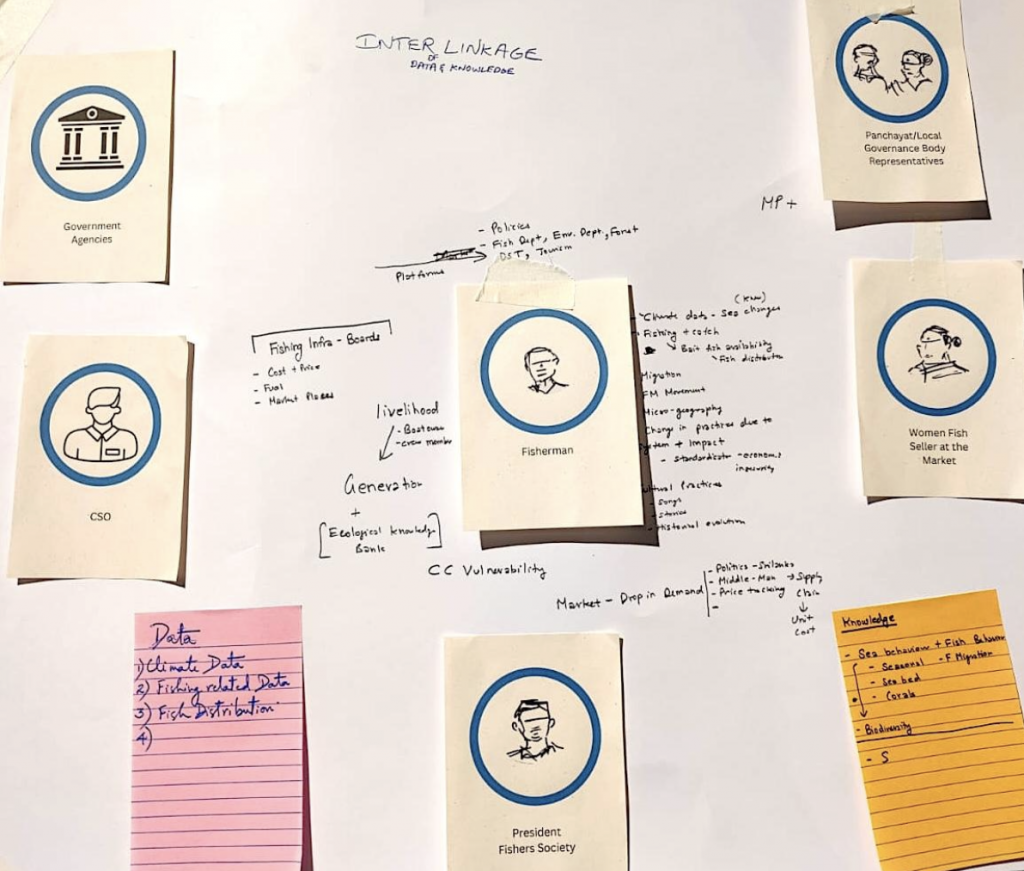

This working session was guided by lessons from a decade-long project by Dakshin Foundation, in Lakshwadeep. Through the anchoring theme on ‘Building climate resilience in small island fisheries through community-led data and participatory governance’, we explored how participatory processes and methods can lead to co-production of knowledge and community ownership of data. For preserving the sustainable “live-bait pole and line” tuna fishing technique practised by the islanders of Lakshadweep, Dakshin Foundation has been supporting the communities by urging them to document their catch through a logbook. This overlays a network of fishing societies, the lifeline of community action in the area. The logbook helps track fish stocks over time and in different sites, enabling fishers to identify patterns and make evidence-based decisions at the local level. While the project has evolved over time, garnering more interest, the discussions in the working session uncovered systemic issues which have made local, community decision-making increasingly challenging. Through the working session, we attempted to understand the lived experiences of the community and uncover the nuances of community-centric data and knowledge systems in small island communities.

The working session was facilitated through a learning case booklet, which the participants used for understanding the learning case in greater depth. Using this knowledge, the participants collaboratively built an artefact to answer the following prompt questions:

- How can the use of participatory mapping blend traditional ecological knowledge with formal data practices?

- Should scalability be the goal, or can smaller, embedded systems be more effective for local governance?

- How can data collected by fishers inform co-management systems in practice?

The working session was designed by drawing from the learning case and also borrowing insights from ‘Meenukarige Booklet’ which documented the process from the sea to the market with actors involved in the process in Kundapura; the booklet was produced as part of the Samagra Arogya initiative in Kundapura, Karnataka by Aruvu Collaboratory in collaboration with Karnataka Health Promotion Trust.

In the session, we encouraged participants to map the roles and responsibilities of the actors involved in the skipjack tuna fishing supply chain in Lakshadweep. The intent was to enable the participants to understand how different people, institutions, and systems interact through the sharing of knowledge, data, and power. In the context of community-based fisheries like in Lakshadweep, this network maps out the key actors involved – such as fishers, fishers’ societies, government departments, researchers, traders, and community monitors – and the relationships that connect them. The working session moves towards a system which can provide equal amounts of bait fish for the fisher folks so they can do away with the unsustainable methods of catching them in the mid-night by using heavy lights to trick the fishes into thinking its day time. These methods can interfere with the ecology of the sea and the future of fishing as a livelihood.

With climate change threatening the livelihoods of small-scale fisheries, fishermen, and other occupations dependent on fishing, there is an increased interest in exploring data-driven methods for better management of fish stocks and fishing-related supply chains, in order for building climate-resilient livelihoods. However, the working session highlighted that knowledge and data are deeply intertwined and complement each other rather than replacing one another. Data helps make experiences visible and supports policy interventions, while knowledge provides intuitive ways of understanding and engaging with the environment. Both exist as part of the same process, since traditional knowledge itself has its roots in observations of surroundings, essentially an early form of data gathering that was interpreted and passed on through generations. The group ended the conversation with how traditional knowledge and data can be used to monitor baitfishing which can create a sustainable practice which benefits the fisher folks and the ecology.

Urban Mobility

The session titled “How do we engage & learn from community knowledge to achieve climate resilient urban mobility?” focused on how community participation and lived experiences can help nuance our understanding of climate change and foster approaches to resilient climate infrastructure. The learning case was put together by drawing from the work of WRI India on the Bangalore Climate Action Plan, launched by Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), to integrate blue-green corridors with non-motorised transport (NMT) infrastructure and the Mapathons, organised for community-led urban greening.

The learning case provoked discussion and facilitated the group to collaboratively imagine possibilities (and challenges) of learning from and engaging with diverse forms of community knowledge as a central driving force for urban climate action. The case was structured along three prompts, as follows:

- What are the diverse ways through which urban communities know the inter-linking between infrastructures, ecological systems and climate?

- What are the forms & practices of community-driven urban climate action?

- How are collaborative community-driven urban climate actions fostered & sustained?

The case first highlighted the interlinkages between mobility and blue-green infrastructures experienced by citizens during climate-related breakdowns. The examples were framed to invite the participants to share more such examples from their work or lived experiences. Second, we shared some glimpses of how citizens have come together and built on knowledge and data systems to respond to climate related disasters in urban settings, followed by sharing Mapathon as a specific example of engaging with community-knowledge.

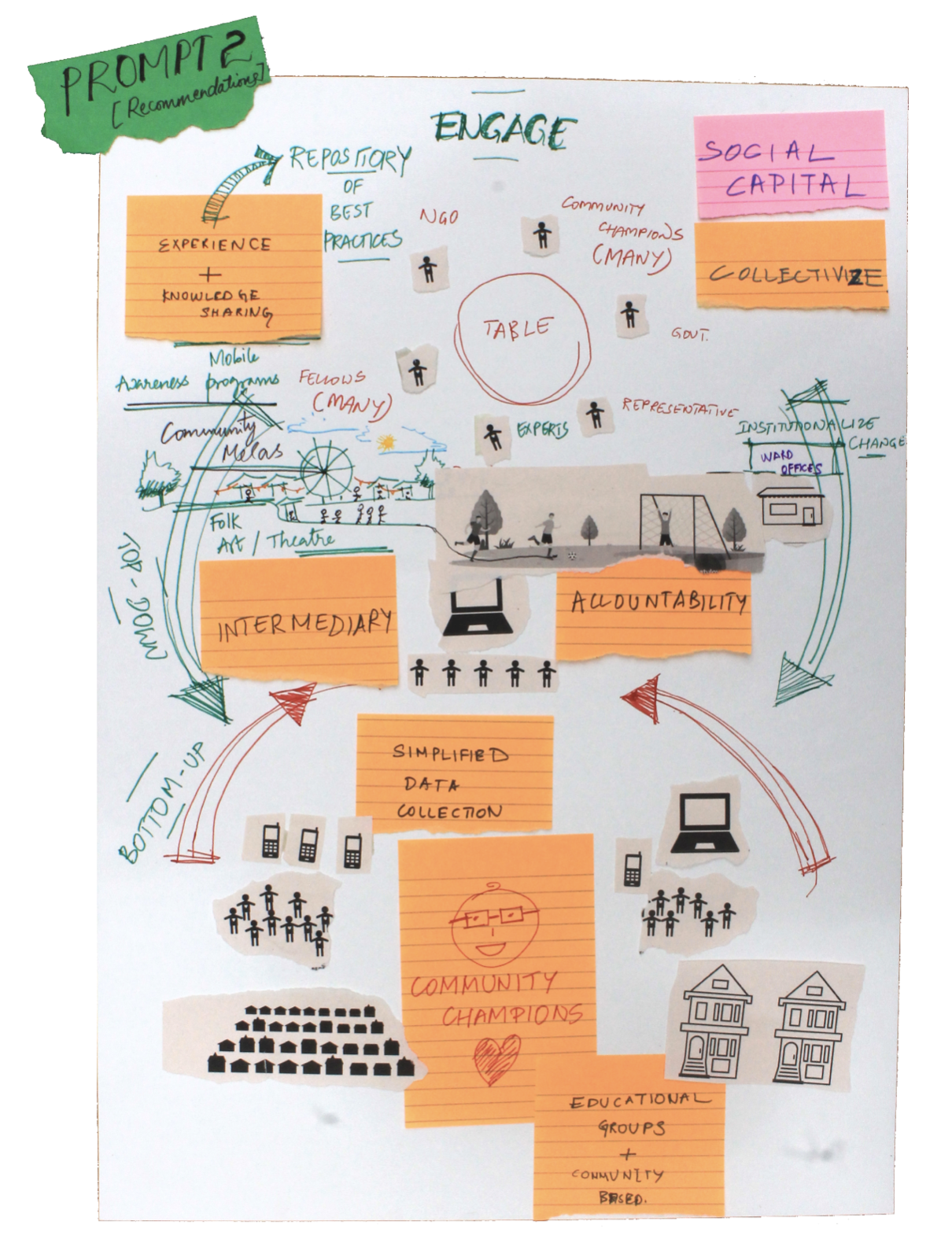

The case used ‘discussion prompts’ as a tool to guide the working session towards collaboratively making an ‘Imagined Map of Climate Resilient Urban Mobility’. The participants were given printed cut-outs of urban infrastructure components and asked to respond to the prompts in two phases: first to map the diversity of knowledge from diverse urban communities, and then to create an imagined infrastructure that considers and centers this knowledge in climate response and adaptation; a map that puts-in-place the human and non-human system ingredients needed for sustained community-driven climate action. Though limited to the experiences from the work of WRI-India, the case was an invitation for the participants to add examples, insights, foresights and ideas from their and other aligned works and initiatives.

Urban mobility is an important area in terms of equipping Indian cities with climate-resilient infrastructure. Data is increasingly being viewed as central to mobility planning. While multiple stakeholder groups are working together to tackle mobility challenges in cities using data, quantitative data have been inadequate in reflecting the experiences of citizens and the socio-economic nuances of how people commute.

The conversations in the working session while making the imagined map highlighted the need to understand the challenges faced by communities such as women labourers, waste-collectors, slum dwellers and people living in low-lying areas or along the edges of water bodies. The participants also drew from their work experience and listed the potential forms of knowledge the communities hold regarding climate-change related breakdowns and how these breakdowns bring forward the interconnections between the blue-green-grey infrastructures. A key insight was that though urban climate response relies heavily on the data produced by the communities most affected by climate change, the interventions do not benefit the communities directly. Participants speculated on certain forms of bottom-up multistakeholder approaches could take, such as participatory community mapping through community champions, co-creating and maintaining community-owned repositories of climate effects, responses and best-practices, and enabling intermediaries between communities and city authorities for accountability of knowledge shared.

Snippets from the panel discussion

In a vibrant exchange the panel unpacked the different facets of community governance of knowledge and data for climate action. The panel consisted of Naveen Namboothri, Dakshin Foundation, Inder Gopal, Center for Data for Public Good, Bhargavi Rao, Independent Researcher, Astha Kapor, Aapti Institute, Vinay Malge, Convenor, Team YUVAA, and Member of the Standing Committee of Wildlife Board, Government of Karnataka and was moderated by Naveen Bagalkot from Aruvu Collaboratory:

The panellists presented different articulations of community knowledge. Vinay Malge shared the story of shepherd in Bidar reading bird calls that indicate presence of underground spring, which resonated with Bhargavi Rao’s experiences with shepherd communities in Chalkere who sensed surface flow of water over seasons through the grasslands, while Inder S Gopal shared the experiences of crowd-sourced sensing of urban air quality. The diversity of examples ranged from very unique knowledge held by grass-roots communities gathered through living with the ecological systems over time, to more recent approaches and explorations of crowd-sources data collection.

The discussion reflected on key challenges towards centring such diverse community knowledge and ways of knowing in climate response. Naveen Namboothri stressed on the need for the climate and related sciences to be reoriented to acknowledge the different epistemologies of community knowledge systems. Astha Kapoor highlighted the need for policy work to integrate oral histories and other forms of lived knowledges as key documentation, while Inder S Gopal highlighted the risks of treating the community as a homogenous entity and to be careful in considering the intent and motivations of the communities in climate data sensing. Vinay Malge brought forward the issue of finding the right people, from the place, who can navigate and mediate between and across the different knowledge systems. As highlighted by Bhargavi Rao, a significant challenge was the mismatch between the climate response systems–which constitutes project definitions, funding cycles, funder expectations, project modalities, etc–and the long-time, slow work of working with communities and their lived experiences.

The central message by the panelists to move forward in building community technologies for climate action was a focus on collaboration rather than incorporation. Astha Kapoor called for incorporating participation across the data pipeline, with strategies such as data cooperatives or collaboratives for social audits of climate data, and community-driven data governance. Inder S Gopal stressed on the need to incentivise urban communities to contribute in data sensing, through clearly communicating the direct benefits of their work. Articulating common motivations and working with the communities to realise the mutual benefits of sharing and centring their lived experiences is a fruitful path forward that Naveen Namboothri shared. Building trust across multiple stakeholders through the long co-creation process is the key. Bhargavi Rao pointed out that such collaborations must emerge from the ground-up rather than be imposed by the governments through top-down policy making; such collaborations are organic and policy must consider the time they take to grow and flourish. Vinay Malge, drawing from the work of Team YUVAA and Living Labs Network, pointed out the possibilities of co-learning between urban students and grass-roots communities that brings forward multiple pathways of collaborative change.

Conclusion

- As the impact of climate change and its inequitable distribution intensifies, there is a need for more dynamic and pragmatic approaches to climate action. Rooting the approaches in community action ensures that the systems and practices we enable and create have equitable impact. Three key learnings emerged for us from the workshop to aid us move towards adapting and adopting community-led approaches:

- Community Technologies are Plural. Rich and diverse forms of knowledge that communities hold in ways of sensing climate shifts and adapting to them. It is important not to reduce this diversity of the forms of knowledge into binaries of qualitative-quantitative, but rather to remain close to the specific forms of the knowledge that show up as cultural signs—oral stories, songs, practices, and other forms of tacit knowledge. Community tech, in this sense, is the diverse ways and practices of knowing each grassroots community. Anchoring our imaginations and the development of climate technologies in such ways of knowing, will be crucial.

- Collaboration over incorporation. There is a need to reimagine how we are framing the role of community knowledge in climate action. The workshop brought forward the pathways where climate research and activism work closely and in collaboration with community-led actions, connecting from across multiple such sites and places, building a ground-up network. Thus, moving beyond collaboration to acknowledgement and bridging of different epistemic traditions, but ways to create systems and practices for mutual benefits and incentives to collaborate.

- Slowness & Long-term Action. Community-led climate action takes time to establish, flourish, and create impact. Structuring of interventions, projects and their funding mechanisms need to consider, and be designed around fostering the long-term engagement between multiple stakeholders and community members.

As we continue to build spaces for conversation on bottom-up data-driven approaches to climate action and pathways for collaboration between diverse stakeholders, a common aspect we keep returning to is consolidating knowledge. Creating repositories of climate knowledge and making preexisting climate data accessible is key to making holistic interventions. Certain aspects that can be considered include:

- Mapping the role of the state institutions: Successful interventions require active participation from government bodies at the different levels, bolstering efforts, providing and creating infrastructure, policy, data, and legitimising community practices.

- Creating a shared knowledge repository on climate data: There is a need to create a common language around climate data and knowledges, and community action. Building consensus on the fundamental aspects of climate change can help develop interventions and initiatives which are specific, scalable, and impactful.

- Envisaging the reliability of data and bolstering pre-existing data flows: There is an abundance of climate data, which exists in silos. Furthermore the idea of what is data has to include the rich and diverse forms of community knowledge. Tech intermediaries need to focus on how to make such data accessible while ensuring it respects fundamental tenets of data governance, and communities creating, collecting, and sharing the data benefit from it as well.

- Ratto, Matt. 2011. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society 27 (4): 252–60. doi:10.1080/01972243.2011.583819.

- Plumb, Donovan. 2008. ‘Learning as Dwelling’. Studies in the Education of Adults 40 (1): 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2008.11661556.