Executive Summary

Trust is necessary to shape robust, citizen-centric public digital infrastructures. As the datafication of migration management and mobility expand, the role of trust in these systems must be further analyzed to understand at which points it must be renegotiated or patched.

This is critical as the digital landscape of migration management is deeply enmeshed in politics of securitisation and control, borne from mistrust and hostility. Revealed through continued deployment of surveillance architectures, tantamount to “virtual prisons”, these compound barriers faced by already vulnerable and precarious populations of refugees, stateless individuals, asylum seekers and other migrants.

Asymmetries of power between governments and the ‘end-users’ of these systems are also worsened by technology – driven by a considerable trust deficit between stakeholders in the migration management ecosystem. Therefore understanding and addressing this fractured trust will be a necessary first step to align on the design and deployment of more ethical and trust-based systems of migration and mobility. Building up trust-oriented infrastructures can serve both destination country public sector actors and people on the move.

This piece aims to both delineate existing patterns of trust, outline what determines its formation and then suggests an initial set of pathways to foster trust between actors.

Introduction

Trust has become a critical pillar in the design, deployment, and adoption of digital public infrastructures. For many of its architects, building for ‘trustworthiness’ has largely been interpreted through a technical lens – arrived at if factors like security, privacy, consent and transparency are addressed. This has led to a panoply of ‘trust’ solutions – ranging from blockchain , distributed ledger and self-sovereign identity systems to cryptographic encryption – as well as technical architectures that seek to verify, authenticate, safeguard and secure transactions, data exchanges and identities. Yet these digital innovations alone will not solve for individuals and communities’ ‘willingness to trust’ these systems – particularly where crises in trust are reinforced by frequent violations, foregrounded by power asymmetries and historical mistrust between entities. These technical solutions must be complemented with accompanying bottom-up community-centric infrastructures, grounded in lived realities and bolstered by digital rights and protections.

Additionally, if trust is to be reconstituted, it must be principally treated as a two-way street, where the ‘willingness to trust’ is strengthened and necessary efforts are taken to build ‘trustworthiness’ between various actors. Secondly, it must be regarded as dynamic and context specific. Digital trust formation is complex and multidimensional and therefore should be framed in a way that is cognizant of socio-political, legal and even psychological experiences that impact its constitution or lack thereof.

In its current state, the consequences of frayed trust are not just harmful for trustors (migrants, refugees) – there may be implications for trustees (public sector) as well. Trust may be broken as a consequence of unintended outcomes that arise as a result of digitisation and ‘private trust infrastructures’, even if this may not have been the intention. Without trust, governments may experience greater friction in streamlining or standardising processes which could build efficiencies around migration management. As articulated in the 11th ASEAN Forum on Migrant Labour hosted in Singapore, “Digital migration management platforms can help reduce the cost and time induced by formal recruitment processes, which too often pushes many women and men to migrate through informal, undocumented, and unsafe channels” Ibid. Building trust-based data infrastructures in migration can therefore support both actors in mutual “value-creation” – an interrelated imperative.

This paper aims to take a closer look at how fractures in trust manifest in digital migration management systems. It is structured in two parts. The first outlines how trust may be conceptualised and constituted. Then, it identifies two simplified flows of trust, where these falter, and what the consequences are for migrants and refugees as well as for governments and other key actors. The second part charts suggests pathways, anchored in the vision for more trust-centric, ethical digital migration infrastructures for all: governments, migrants and refugees. These include empowering trusted intermediaries and strengthening communal modes of trust-production and building flexibility within digital migration systems by identifying new methods and indicators for trust. Arguably, these engagements are first steps towards establishing trusted digital infrastructures – the composition and design of which merit further research beyond this piece.

Unpacking digital trust and its production

Trust is a complex and multi-dimensional concept that is best understood as a process or set of logics. It’s also useful to consider trust as a dyadic relationship between a trustee (the entity that must produce trustworthiness) and trustor (that must have the willingness to trust) that may be reciprocal, mutual or asymmetric in nature. In the context of digital trust, this dynamic is defined by the World Economic Forum as: “an individuals’ expectation that digital technologies and services – and the organizations providing them – will protect all stakeholders’ interests and uphold societal expectations and values”. Beyond this, there is an assumption that givers of trust (trustors) possess a degree of agency in evaluating ‘expectations’ of the technologies’. There may be a trade-off made between how potentially useful the technology is and the probability of it causing harm – this could range from individual injury, societal injustices or more systemic violations of rights and associated beliefs.

Further, understanding how trust forms and breaks in the context of digital infrastructures and systems requires a broad mapping out of what has been described as the ‘digital nervous system’ comprising both state and non-state actors in the digital migration management ecosystem as well as their online and offline extensions. This includes but is not limited to: governments(transport/mobility agencies, law enforcement, immigration departments, border control authorities), civil society (advocacy groups, humanitarian agencies, multilateral institutions, research institutes, non-governmental organisations), private sector (social platforms, telecom providers, technology companies) and individuals and communities (refugees, migrants, collectives).

Additionally, there are various logics by which trust may be produced: public, private and communal. Publicly produced trust is seen as a responsibility of the state and its related extensions to create freely for the public. Private producers of trust leverage methods like building familiarity with their customer and reputation to build trust for a fee in a service or product. Lastly, communal trust is produced inter-group for the groups benefit – groups can range from collectives, unions or other familial, ethnic, religious, tribal associations. These productions are important to contextualise as they can help point to where trust needs to be reconstituted or strengthened.

Mapping trust flows in migration and their consequent impact

Migration is often traditionally typified across the following categories: international, national, local, voluntary and involuntary. This piece focuses on trust in the context of international migration that may be voluntary (for e.g economic/environmentally driven) or involuntary (including refugees, IDPs and asylum seekers) in nature. The figures below showcase two simplified flows within the mobility and migration ‘digital nervous system’. Flows will be evaluated on the basis of four aspects highlighted by OECD that can build and maintain trust. These include: transparency, ethics, privacy and consent.

Figure 1: Trust flow from destination country governments (Trustee) to migrant and refugee communities (Trustor)

Figure 1 depicts a frayed trust flow, between the trustor and trustee. Most studies examine public productions of trust between governments and “citizens”. In the context of migration and mobility, trust is framed by certain actors (media, political parties) as a heightened expectation of governments by citizens to keep them safe from potential threats like terrorist attacks. Enhanced screening protocols, and other forms of ‘security theatre’ at points of transit, entry and exit are often the responses adopted by governments to illustrate “taking action”, thereby fostering citizen trust in public leaders.

Yet, it is arguable that many state actors are not incentivised to “produce” trust for individuals or communities that are non-citizens. As illustrated in Figure 2 below, the first faultline in the migration and mobility landscape are that ‘citizens’ and possibly ‘Third Country trusted travellers’ are viewed as the primary and often sole ‘Trustors’, and migrants and refugees are relegated as secondary or non-existent in the trust dynamic.

Figure 2: A hypothesised comparison of trust flows between ‘citizens’ and ‘migrants & refugees’ in migration and mobility systems.

To take a closer look, Harwood’s summation of trust “as policy is built on the set of dispositions that we consciously hold towards individuals and groups” can be considered. Policy developments such as the EU’s ‘Global Approach to Migration and Mobility’ have previously recommended a balanced approach and human rights orientation of both irregular, regular migration along with international protection and asylum. In practice, however, migration is criminalised which trickles down into the design and choice of digital infrastructures built and deployed.

Specifically, a report released in 2020 by the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance highlights how “digital technologies are being deployed to advance the xenophobic and racially discriminatory ideologies that have become so prevalent, in part due to widespread perceptions of refugees and migrants as per se threats to national security. In other cases, discrimination and exclusion occur in the absence of explicit animus, but as a result of the pursuit of bureaucratic and humanitarian efficiency without the necessary human rights safeguards.”

Many of the sophisticated security architectures being designed and deployed by destination countries are often done in tandem with private sector vendors. Arguably, the design of these architectures may be undergirded by a fundamental distrust of the “Other” or “undesirables” – refugees and migrants. These are often discreetly adopted by governments often with limited transparency, oversight or legislative approval or accountability. Governments in the UK and Netherlands have recently been criticised for experimenting with algorithmically driven risk scores to screen applicants, which raises questions around both the sources of data and how they are used to arrive at these decisions. Questions of ethics, privacy and consent are also brought to the fore with projects that leverage more invasive forms of bio surveillance, including thermal cameras, CO2 monitors, bone scanners etc. Here, consent and its capture are often overlooked as refugee and migrant populations are treated rather as a ‘technological testing grounds’.

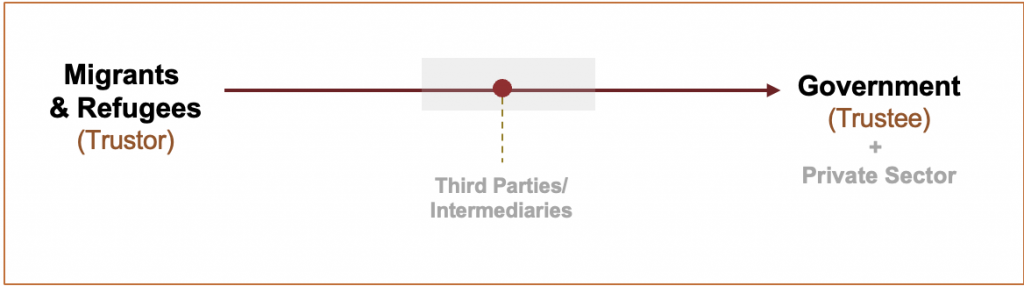

To break with the often unidimensional framing of trust, its necessary to also unpack the trust relationship as it flows between trustors (migrants and refugees) and trustees (destination country government). Addressing barriers to trust (and lived experiences around its violations) and mapping entities involved in making or breaking it can help identify opportunities for value-creation and drive the design of data infrastructures that are responsive to needs of trustors as well. Figure 3 attempts to visualise this complex relationship where the logics of trust production are not as straightforward – and often mediated or formed by multiple stakeholders.

Figure 3: Trust flow between migrants (trustors) and destination country government (trustee)

Trust violations and traumatic experiences that constitute distrust are also formed at several junctures of a refugees journey, both before and through migration management systems. For refugees and asylum seekers, fundamental ethical concerns have arisen as a result of datafication and growing use of monitoring tools at borders by nation states or tracking and surveillance technologies embraced by law enforcement agencies at airports. The determinants that constitute a dynamic of distrust or fractured trust have been extensively studied in context of digital identity – where between the ‘trustor’ (migrants, refugees, stateless peoples) and ‘trustees’ (government agencies, border authorities, private digital ID companies/vendors), numerous privacy challenges, bureaucratic biases and instances of discrimination as a result of digital ID tools and platforms have emerged.

Impact of broken trust in digital migration management systems on migrants, refugees and asylum seekers

In addition to these infrastructures offering individuals little control or agency, there is also considerable dependency on these systems. For instance, the possession of a verifiable identity – whether affirmed by officials online or offline – is integral for asylum seekers in their journey towards seeking protection. As articulated by Hollins, a Protection Visa Case Officer at the U.S Department of Home Affairs, “those most in need of protection are often those with the most limited access to documentation that verifies their identity to an administrative standard”. For economic migrants seeking employment, verification of credentials, degrees and other documentation is often necessary by potential employers, governments, and possibly even third-party intermediaries. This dependence on these often-restrictive systems, offer little in the way of choice in alternative approaches of verification and credentialing.

Emerging pathways for trust-building in digital migration systems

While discourse on trust-building in digital migration management is still nascent and requires greater inquiry, a few pathways to initiate trust-building are shared below:

- Deepen access and accessibility of digital infrastructures by experimenting and adopting multi-stakeholder innovations – Access is a fundamental precursor to building trust and currently operates as an obstacle for many migrants and refugees. In addition to the possession of a device and reliable connection to the internet, the availability of clear and accessible communication and guidance on how to navigate systems – online and offline – is imperative. Tarjimly, an app which connects refugees to global volunteer translators has recently partnered with Boeing, to expand its network of multi-lingual translation support in real-time and improve its app’s user interface. Their goal is to ‘democratize language access for displaced persons globally’, while acknowledging that “language shouldn’t be a reason for denial of service”. Other communication solutions may draw on a combination of low-tech dissemination techniques and dispersal through community infrastructures. A review of UNHCR’s innovative field approaches illustrate that ‘two-way’ communication solutions can involve loudspeakers, digital displays and face-to-face engagement with translators. While their research suggests face-to-face engagement is preferred and must trusted amongst refugee populations, digital solutions that are cognizant of cultural and linguistic context or cues may help to put people at ease. For instance, ‘Translation Cards’, an app which have been designed to operate in low-bandwidth settings, has provided humanitarian actors with the ability to create multi-lingual translations of frequently asked questions, displayed through audio-visual flashcards. These digital tools may free up translators time, and in other cases, supplement a lack of linguistic support/skill of other actors on ground – vital to bridge both access and eventual trust gaps.

Identify trustworthy actors or ‘mediators’ for the delivery of information and consultation – Considering that productions of trust are relational, understanding who may already be considered a ‘trusted source’ is necessary to leverage and eventually transfer trust to other digital systems and intermediaries. Those regarded as ‘trustworthy’ or ‘untrustworthy’ actors may differ from community to community. A study in Australia focused on creating accessible COVID-19 information for their diverse, multi-lingual citizenry found that official interpreters/translators were not seen as objective intermediaries by refugees and asylum seekers but instead as colluders with the government. Instead, many refugees preferred to use their own online translation tools to verify information shared. The reception and provision of health information by refugees and migrants was better received from healthcare professionals over official government representatives. Similarly, community and religious leaders were seen as more trustworthy actors that could enhance the trustworthy delivery of information/messages. In other contexts, community enumerators or refugee data gatherers such as those part of Mixed Migration Centres’ 4Mi initiative, operate with existing trust and access to ‘hard-to-reach’ populations. Due to their existing community tether, these enumerators can deliver information, consult with refugees and migrants on the move and have a deeper understanding of their realities, needs and histories – necessary to contextualise and provide accurate information and advocacy down the line.

- Enhance and explore flexibility within digital migration systems and processes – Particularly for asylum seekers who do not possess passports or forms of identity, a few countries are exploring expanding the sources of data used to verify identification. Recently, Switzerland’s immigration has been given the ability to access digital data stored on smartphones to authenticate asylum seekers ‘identity, nationality or itinerary’, which if carried out without guardrails may result in unchecked surveillance. Australia’s financial intelligence agency, AUSTRAC provides an alternative, ‘risk-based’ approach to support customers’ that do not possess standard identification in order to access financial services. Certain provisions have been made particularly for Aboriginal communities. Those classified as ‘low-risk’ in money laundering and terrorism financing may verify their identity through: referee statements from reliable and independent people (e.g religious leader, police officer, community lawyer, manager of a refuge accommodation, health professionals etc) or self-attestation in some cases. Flexibility in these provisions, particularly for asylum seekers and migrants with intersecting vulnerabilities is necessary for inclusion, equitable treatment and can bolster trust in broader systematic processes and eventually institutions.

- Empower existing trusted intermediaries or digital stewards – Stewards can be conceptualised as institutions that possess close ties with communities and often possess a duty of care towards their beneficiaries (migrants, refugees etc), therefore are likely to also have existing patterns of fulfilling trust. These stewards may present opportunities for greater representation, advocacy and agency around data-related migration systems. Therefore, to enhance access for disconnected migrant or refugees to digital migration systems through “trusted sources”, first stewards must be identified and second the potential of stewardship in migration must be explored. Stewards’ form and function may range. This section focuses on potential stewarding entities under two broad categories: non-state established institutions and community networks/structures.

3.1 Established, non-state intermediaries in migration data ecosystems

Financial institutions, private sector organisations, research or educational institutes can play a critical role in expanding earlier mentioned flexibility in migration data ecosystems. These actors possess required data assets that can act as alternative sources or “trust indicators” in verifying identity, educational/skill qualifications, financial status, and nationality. These intermediaries may also possess relationships of trust potentially with both governments and migrant communities, acting as important bridge that can facilitate secure data sharing while also rendering greater transparency, agency and possibly security over data and its governance. Details and on who these providers of “trust indicators” may be and how they can meaningfully engage with people on the move, governments and other stakeholders are in the process of being further conceptually defined by experts in a note on Shared Mobility Spaces (available for reading upon request).

3.2 Community Networks: E-diaspora and digital migrant communities

Digital diaspora communities are characterised for being able to “recreate and expand a diaspora’s sense of shared identity and community by providing a virtual venue for affirmation and recognition.” These communities are vast and multidimensional – the e-Diasporas Atlas, a research project incubated by Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme ICT Migrations program, categorised over 8,000 migrant websites – which in some ways represent the non-monolithic characteristics of migrant communities, interests and experiences. Yet central to these communities’ framings are the positioning of members of these spaces as ‘connected users’ or participants with the agency to shape, share and archive information on social, economic and cultural needs.

In digital migration systems, these communities can play several roles in supporting people on the move in navigating and having greater agency over their digital and offline journeys. Some governments like Australia are exploring how they can engage with e-diasporas to share or circulate verifiable information, interact with community leaders to assess welfare needs and serve as a robust feedback loop for migrants to share concerns and receive guidance on legal and regulatory processes.

E-diaspora networks are also described to possess network effects both ‘online’ and ‘offline’. With some of these networks, where resources and capacities permit, these spaces have been used by migrants to mobilise, distribute content to support other members embarking on their immigration journeys or in integrating in their destination countries. As an illustration, the Tayo project, a platform that tackles misinformation and delivers culturally responsive health information and guidance is, built by and for the Filipino diaspora and migrant community.

Deconstructing and thwarting misinformation can have positive impacts on trust in both trust flows – destination country governments (Trustee) to migrant/refugee communities (Trustor) and that between migrants (trustors) and destination country government (trustee) – visualised earlier in the piece. Where for the former, it can be a powerful tool to subvert narratives, tropes and dangerous forms of rhetoric (fake news) that prevent governments from seeing people on the move as worthy of protection, rights and needing to being holders of their trust. Positive narratives and dignified representations of their lived realities are necessary for improving ‘levels of solidarity and acceptance for migrant communities’ For migrants, trustworthy information and trusted spaces, particularly in the digital ecosystem are necessary to safely navigate mobility systems and receive the full protection they are entitled to under international humanitarian laws.

There may be further opportunities and use-cases to explore how the digital and e-diasporas can play an important role in contributing to migration management at various junctures both pre-departure, arrival and during integration of migrant communities in destination countries.

In addition to stewards, ecosystem enablers are necessary to support capacity building efforts, drive co-design and foster partnerships between actors – all critical activities to generate ecosystem trust in the migration landscape. The Hive Innovation Lab, affiliated with UNHCR USA is carrying out this work through a few streams: hosting a platform for new data innovations through hackathons, piloting ideas and creating prototypes through multi-stakeholder partnerships and building a data advisory board to guide responsible and technically novel data governance. The Lab has also created an important feedback loop and co-design philosophy by engaging with potential other ‘stewards’ or intermediaries that advocate and represent migrant communities, like Refugee Congress. The active inclusion of refugees and migrants as ‘end-user’ groups in this way can support the design of responsive data infrastructures that are trustworthy-by-design.

Conclusion

To refer back to one of the productions of trust, it can be conceived of when a trade-off is made regarding the potential use of technology and the possibility of it causing harm. Considering the overarching goal of building trust-based digital migration for all, policymakers, builders of these systems and civil society must be cognizant of both sides of the coin – harm and value. Therefore, part of the way forward will be to visibilise data infrastructures for migration infrastructures and understand how these data-led migration systems and interfaces affect people on the move. This analysis can help to reveal where interactions with these infrastructures may result in digitally induced or furthering systemic harms or exclusions.

In parallel, opportunities must be explored for how mutual value may be created for all stakeholders that seek to create fairer systems for human mobility. This will require further research to understand, challenge and reassess the intentions and limitations in vision (of all stakeholders) around how technology and data can be responsibly leveraged and governed. A critical piece in this puzzle will be to critically engage more with possibilities of stewards, intermediaries, and community-oriented data infrastructures.